Essays From West of 98: Freedom

On making history, a multigenerational struggle for freedom, and living in community

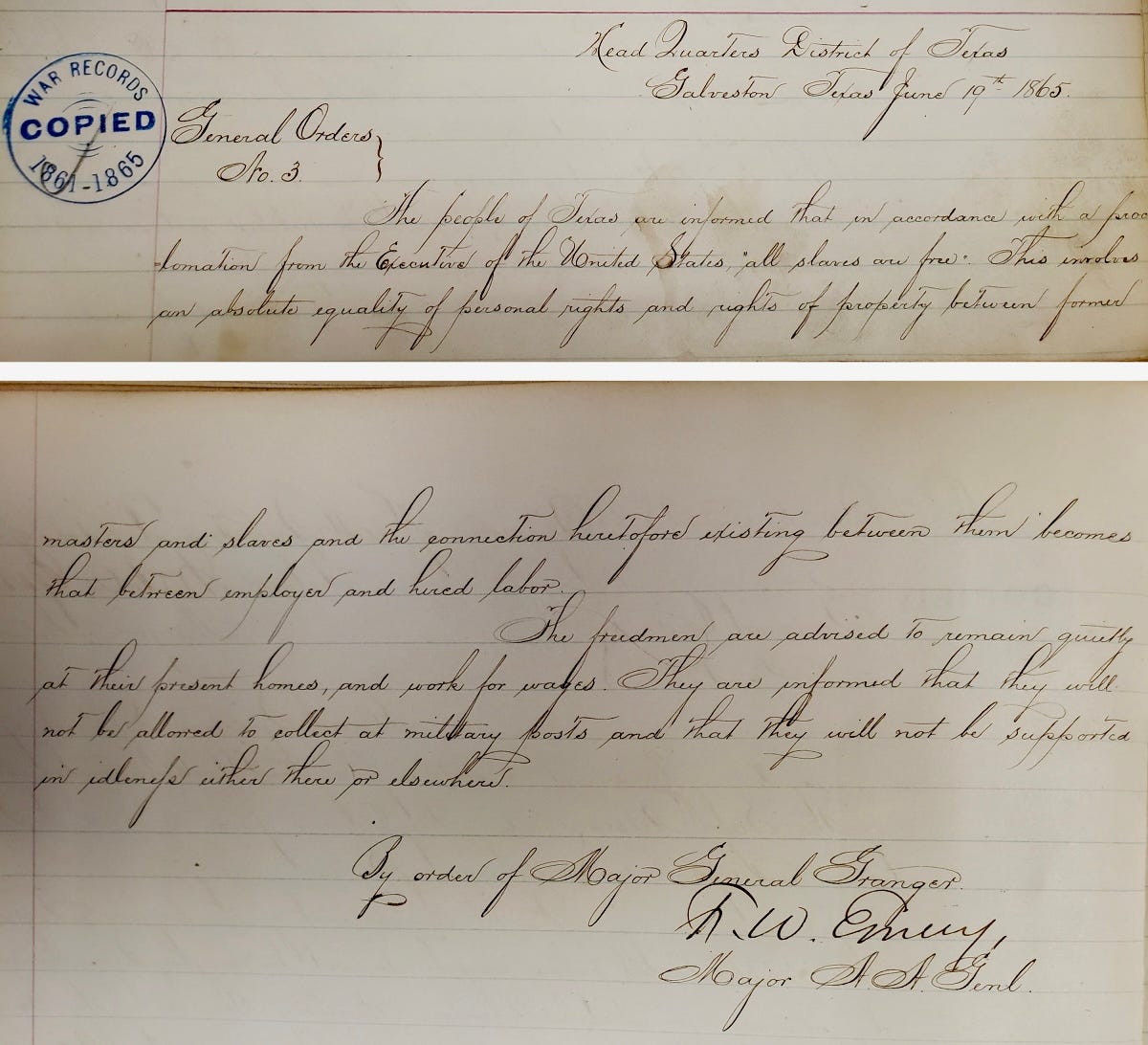

Headquarters District of Texas

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865

General Orders

No. 3

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

By order of Major-General Granger

F. W. Emery, Major & A.A. Gen.

Making history is a funny thing. By nature, “history” is a prism through which we look back in time. It is not always evident in the moment that a person is “making history.” It may take some time, even many years, for all the dust to settle and the momentous nature of a moment to become apparent. When the Declaration of Independence was signed on July 4, 1776, it would be seven long years before those fifty-six men learned whether they had changed the course of world history or signed their own death warrants. Abraham Lincoln knew the stakes when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, but he was still trying to turn the tide of a bloody and vicious war. Much blood would be shed before the end, including Lincoln’s. He had been dead by John Wilkes Booth’s bullet for just over two months when General Granger arrived at Galveston.

Did General Granger know that he was making history? Surely he knew that he was entrusted with an important task. He was arriving as part of a massive military occupation of territory that had been in open rebellion. It would not be less hostile to Federal soldiers simply because the fighting had ended. He was delivering a message that would liberate a group of people who had been held in bondage for their entire lives. News traveled slowly, so one can only wonder whether Granger knew this was the final group of enslaved people in the United States of America. He may not have even contemplated the immediate status of enslaved people in the other states. I doubt he considered that his General Order No. 3 would be the centerpiece of a national holiday just over 150 years later.

As we all know, General Order No. 3 did not end the struggle on that day. Reconstruction, Jim Crow, “separate-but-equal,” desegregation, and a massive civil rights movement would lie ahead over the next century. Stamford, Texas did not exist on June 19, 1865, but it would be touched by the good, bad, and ugly of that struggle. Through that struggle, our community is full of stories and experiences that are worth considering, sharing, and honoring.

In “The Work of Local Culture,” Wendell Berry writes something particularly important to me today:

“[W]hen a community loses its memory, its members no longer know each other. How can they know each other if they have forgotten or have never learned each other’s stories? If they do not know each other’s stories, how can they know whether or not to trust each other? People who do not trust each other do not help each other, and moreover they fear each other. And this is our predicament now.”

May we use Juneteenth as an opportunity to learn, know, and cherish each other’s stories, even if those stories can be uncomfortable to hear. By doing that, we come to better know one another. We learn to better trust one another. And most importantly, we strengthen the bonds of living in community together.

James Decker is the Mayor of Stamford, Texas and the creator of the West of 98 website and the Rural Church and State and West of 98 podcasts. Contact James and subscribe to these essays at westof98.substack.com and subscribe to him wherever podcasts are found. Check out the West of 98 Bookstore with book lists for essential reads here.