Essays From West of 98: American Idol, Part 2: Tragic and Alone

Romantic heroism is at the heart of the Western. What are its perils?

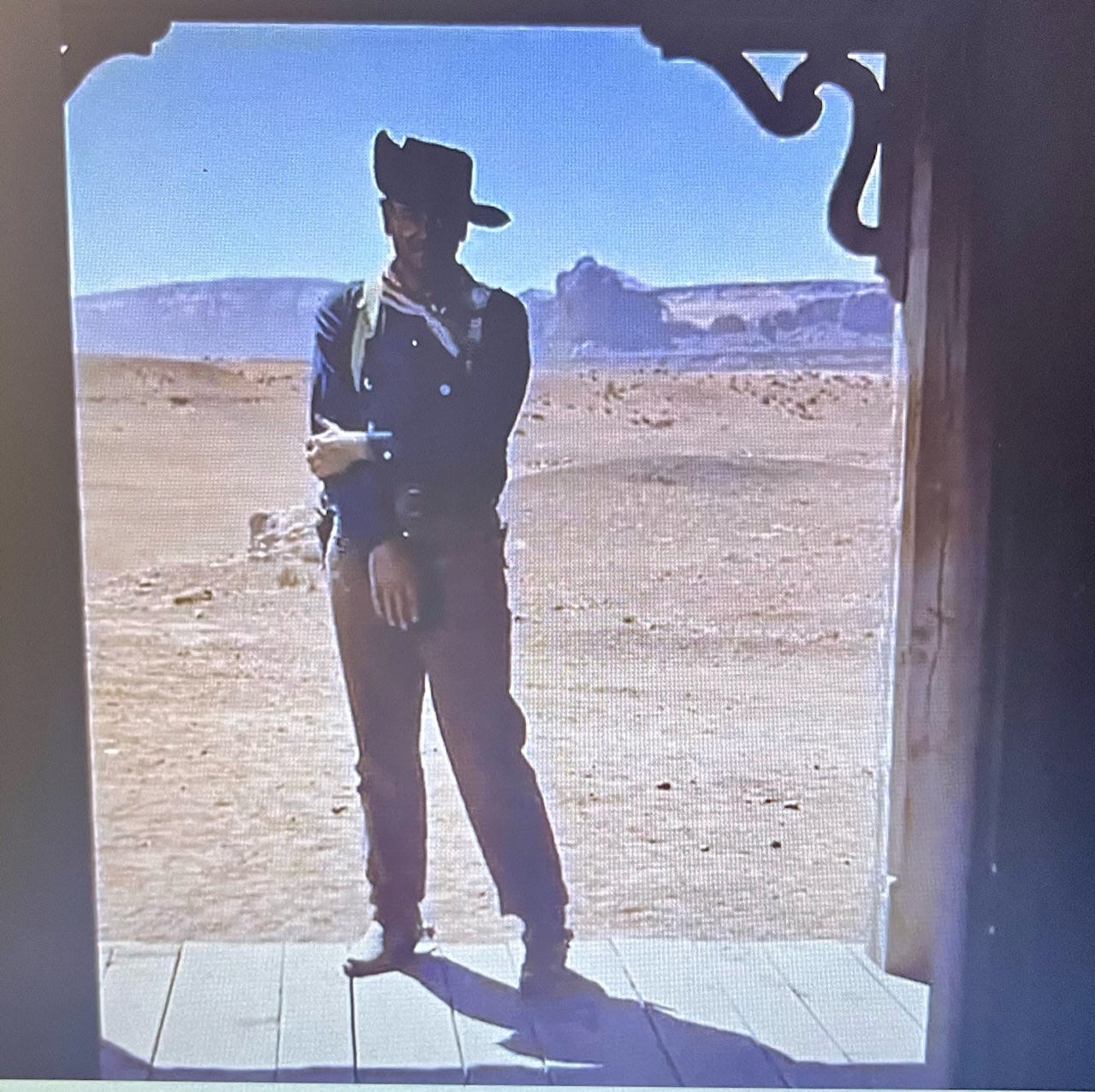

The ending of John Ford’s epic 1956 “The Searchers” is one of the most famous scenes in Western film. John Wayne portrays Ethan Edwards, a Civil War veteran who spends years hunting his niece Debbie, who was abducted as a child by Comanche raiders. After a bloody battle, Ethan removes Debbie from the Comanches and he delivers her to those she knew as a child.

In the final moments of the film, everyone walks into the house, except for Ethan. The great Sons of the Pioneers sing “ride away, ride away, ride away…” Ethan watches the others for a moment and stares into the house. Then, he turns away. As he strides back towards his horse, the door swings shut and the screen goes black.

It is incredible filmmaking. It is also terribly sad. Ethan Edwards turns his hunt for his niece (and his hatred for the Comanche people) into an obsession. That obsession leads him to do some brutal things during the film. He devotes his life to finding his niece, and he does, but he loses more than a little of his humanity along the way. His choices leave him alone in the end. In the final scene, Ford depicts a man who is unwilling to join his friends and loved ones. The spirit of family and community is either no longer within him or he feels unworthy of that spirit.

The Western is sometimes criticized as shallow, two-dimensional storytelling. In part, that comes from judging the genre by the lowest common denominator. As I mentioned last time, the Western is rife with unimaginative, formulaic, and fantastical plots. But those are not the ONLY stories told in the Western. Films like “The Searchers” tell complex narratives with more than a few shades of gray between black and white. On the surface, it is easy to look at Ethan Edwards and see a bold, daring, heroic figure. He was the archetype of the “rugged individualist” unafraid to face challenges and set out alone. In the end, John Ford shows the potential sadness, too.

I have written in the past about the perils of “rugged individualism” and there are few better examples of the peril than that final scene of “The Searchers.” Ethan Edwards gave everything he had to search for his niece and avenge the bloody raid on his people. In the end, he was left with only that.

Last week, in the comments to my essay on Facebook, my friend Jerod McDaniel observed that there is an internal struggle that comes with the romantic isolation of the West. People (individually and collectively) need heroes. We can long for heroes and attempt to create them out of the romantic isolation of our own lives. We are so tough and bold that we don’t NEED other people. We can go it alone. We can brave any challenge or danger that besets us. We are just like the brave heroes who settled the frontier before us! That can be a powerful feeling. When the spring winds howl, when the dust or hail storms rage, when a year’s worth of rain comes in a week, or when the native flora and fauna are predisposed to spines, stingers, and poison, it is hard not to valiantly channel the spirit of your forefathers in the West.

But as Jerod and I discussed, these concepts can be both powerful and toxic, depending on how they are used. We can channel the heroism, romance, and idealism of the cowboy into a force for positivity in our lives and in our communities. That is something to work towards and be proud of. But if we channel these qualities the wrong way, then we might end up a tragic and lonely figure like Ethan Edwards. Our communities and society are worse off when these qualities are emphasized in the wrong manner.

Next week: Louis L’Amour, Elmer Kelton, and the heroism of the everyman.

James Decker is the Mayor of Stamford, Texas and the creator of the West of 98 website and podcast. Contact James and subscribe to these essays at westof98.substack.com and subscribe to West of 98 wherever podcasts are found.