Essays from West of 98: The De-Butzification of Rural America

It's time for change in American farm policy

A much older version of this essay was published in 2022. As part of my restatement of principles for West of 98, and with certain economic and political circumstances afoot in the world, I thought now was the time to reiterate these ideals.

“Get big or get out!”

In the course of American history, I am unaware of any other single, simple phrase that so succinctly described a policy that was so destructive for so many people and communities. I do not exaggerate. These five words have unleashed 75 years’ worth of decline and destruction on rural American communities, economies, and health, the effects of which are even more apparent today.

It started with Ezra Taft Benson, the Secretary of Agriculture under President Eisenhower. Benson was the first known person to utter the words “get big or get out” to American farmers. Benson declared that the era of small farming was over and he crafted American farm policy to ensure that was the case. In 1971, this idea became fully entrenched in farm policy when Benson’s former deputy Earl Butz was named Secretary of Agriculture. Butz was loud, he was confident, and he was something of a bully to anyone who had ideas that differed from his own. He decried small farms as archaic. He announced that America had too many farms. He berated farm audiences with the “get big or get out” phrase. He thundered away to farmers with the zeal of a revivalist preacher, shouting to “plant fencerow to fencerow” and turn every acre of land into cultivated crops.1

Surely this was because he sought to maximize the prosperity of the American farmer, right? Nah.

Benson and Butz were administrators of American farm policy at the height of the Cold War and in the aftermath of World War II. Postwar economic planners were eager to turn American industrial might (in part the source of victory in battle) towards civilian needs, including the mechanization of agriculture. By unleashing a new world of mass-produced tractors and industrial fertilizers (to replace tanks and artillery shells in the factories), American agriculture could produce crops at great quantities and low prices. That cheap food could be used as part of geopolitical strategy to combat the encroachment of communism from the Soviet Union to the developing world.

Once you increased agriculture’s mechanization, a farmer could manage more land (get big!) with fewer humans in his employment, and human labor could be “encouraged” to move away from the antiquated rural life and into the growing factories of the cities. The farmers who were unable or unwilling to adapt had to, well, get out. And as the entire system—government policy, academic research, equipment and input suppliers—reoriented itself around this new landscape of agriculture, it became a bit of circular logic operating on itself. Getting big meant getting bigger, getting cheap meant getting cheaper. Everything improved except the farmer’s bottom line. It drove farmers out of business and people out of rural communities slowly and steadily, punctuated by mass crises like the 1980s farm crisis. The bleeding occasionally slowed with an unexpected bumper crop or a turn of good fortune in crop prices, but the steady decline continues. Government farm programs are often called a “safety net” but in reality they’re more of an emergency responder who picks up the injured fighter off the ground and gives him smelling salts before pushing him back into the ring for another round. That analogy may be blunt and harsh, but it is reality. Just talk to a farmer friend.

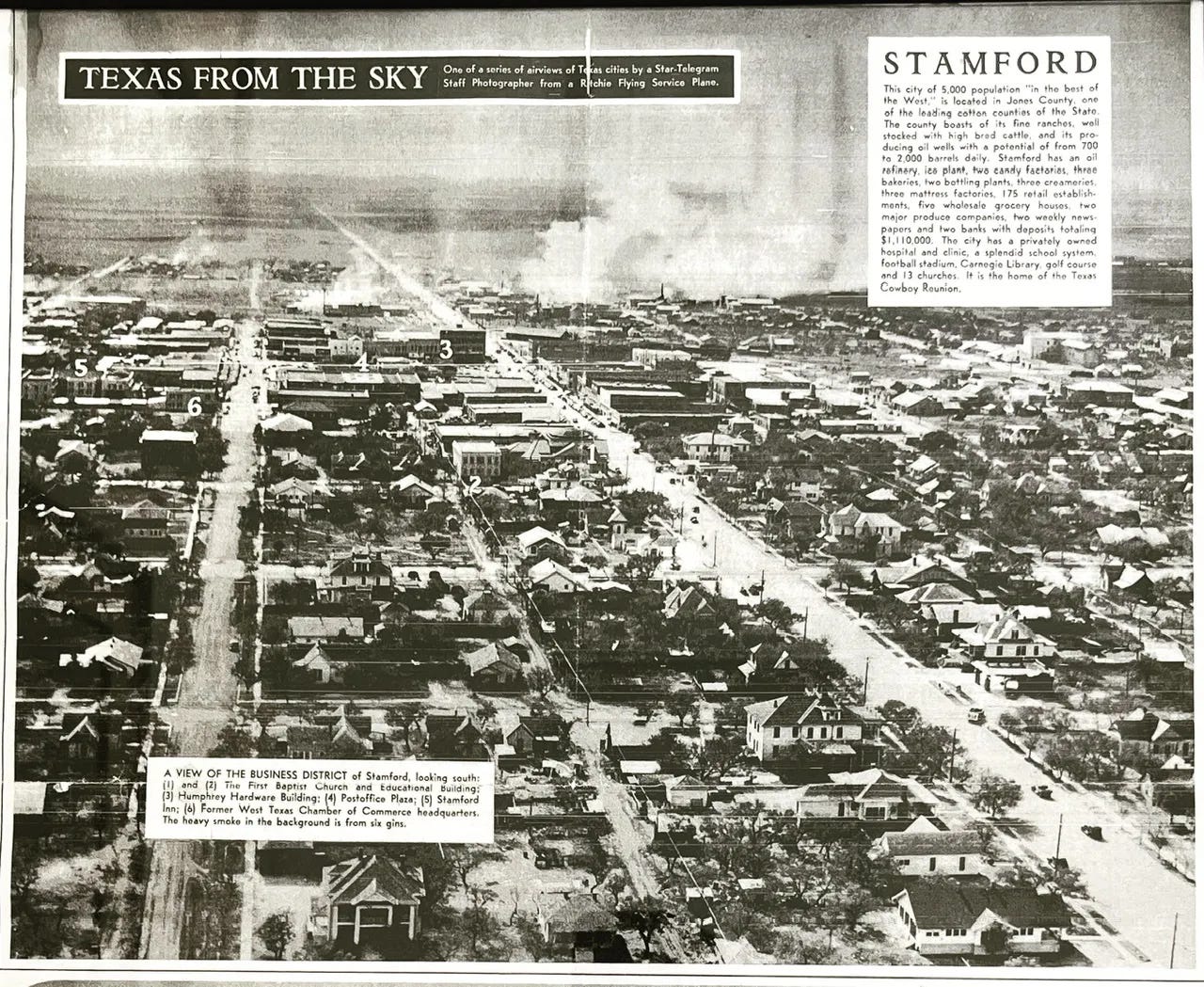

Today, Earl Butz is rightly viewed as a villain in American agriculture history.2 It is not all his fault, though. Butz was loud, obnoxious, and glad to be out front, so he serves as an avatar for many in agriculture policy who agreed with him and did the same work that caused so much economic damage and population decline in rural communities. You may be reading this and wondering why this matters to you if you were a rural citizen who never owned a farm. Well, that farmer who once employed several farmhands? He no longer employed them. And when his neighbor went out of business, his neighbor no longer employed any farm hands. That farmer started farming the neighbor’s land, but it took fewer people and more tractors. All those other people moved away. They stopped buying clothes at the dry goods store. They no longer bought groceries or got their hair cut at the barber or went to the movies or owned a house or paid property taxes or sales tax. That affected the livelihood of the grocer and the shopkeeper and the barber and the theater owner. All those people stopped visiting the local doctor and lawyer and dentist. All those people or their employees had children enrolled in the local school. Those children left and went elsewhere. Suddenly the livelihoods, lives, and destinies of countless people, none of whom ever drove a tractor or hoed a row of cotton, were adversely affected by the ideals of men in Washington, D.C. who believed the world was better with fewer farmers. Maybe the world was better as a whole. Certainly, many people got richer. But places like Stamford, Texas were not better. Places like Stamford, Texas dropped in population from over 5,000 at the 1950 Census to less than 3,000 at the 2020 Census as a direct result of these policies.

As we all know, a new presidential administration will soon commence in Washington. Farmers are waiting for a new Farm Bill to be passed after months of delays and do-nothingness in Congress. Farmers are asking for additional relief to combat massive crop failures and devastating crop prices. These things impact our rural communities far beyond just the individual farmer’s bank account. History has shown us that.

“Get big or get out” is still the underlying vision of American farm policy and it continues to gut places like Stamford. It is time to dispense with these disastrous ideas perpetuated by the likes of Benson and Butz. A De-Butzification of farm policy is desperately needed. Before the era of “get big or get out” and “cheap food,” the prevailing ideal of American farm policy was prosperity in rural communities. Let’s bring that back, while we still have rural communities left to prosper.

James Decker is the Mayor of Stamford, Texas and the creator of the West of 98 website and the “Rural Church and State” and “West of 98” podcasts. Contact James and subscribe to these essays at westof98.substack.com and subscribe to him wherever podcasts are found. Check out the West of 98 Bookstore with book lists for essential reads here.

This merits its own essay, but a major lasting impact of this policy was to obsessively seek new outlets for cheap commodities, notably corn and soybeans. Replacing cane sugar with high fructose corn syrup as a sweetener in sodas? That’s all Butz and Friends.

For more on this topic and the peril of “get big or get out,” Wendell Berry’s “The Unsettling of America” is the core text. If you have read these essays or followed me on Twitter for long, you know my utter disdain for Earl Butz. I am downright chummy with Butz compared to Berry.

Amen. De-butz it and re-HenryWallacize it!

The description of the town sounds very much like Athens Texas where I grew up, down to the kind of manufacturing. Today it is little bigger but revolves around some ranching and tourism/second homes from Dallas