Welcome to West of 98! If you are new here, read more about my Substack here. If you have not read my letter to new Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins, I recommend it. Every month, I summarize my writing and a few good reads and recommendations here.

I’m writing this newsletter in the middle of May, which is Mental Health Awareness Month. I’ve written about mental health in this space on many occasions and I will continue to do so. It is vital that our communities consider every aspect of our health and wellness if we want to create true rural revitalization. Back in the spring of 2023, I wrote a series of essays called “American Idol.” This series focused on the mythos of the American cowboy in literature and cinema and its influence on modern culture, particularly rural culture. In it, I covered the origins of the Western, the distinctions between Louis L’Amour and Elmer Kelton, the complicated legacy of Lonesome Dove, the positive aspects of the cowboy ideal, and John Wayne.

Below I have re-published and slightly expanded on that John Wayne essay, because it covers something vitally important to the idea of mental health in our communities: tragic loneliness. Please read this and enjoy! If you read the original essay in 2023, I encourage you to read it again, because there is plenty of new information. Stay tuned later this week for this month’s edition of the Prairie Panicle and in weeks to come for essays on sports fandom and Rerum Novarum.

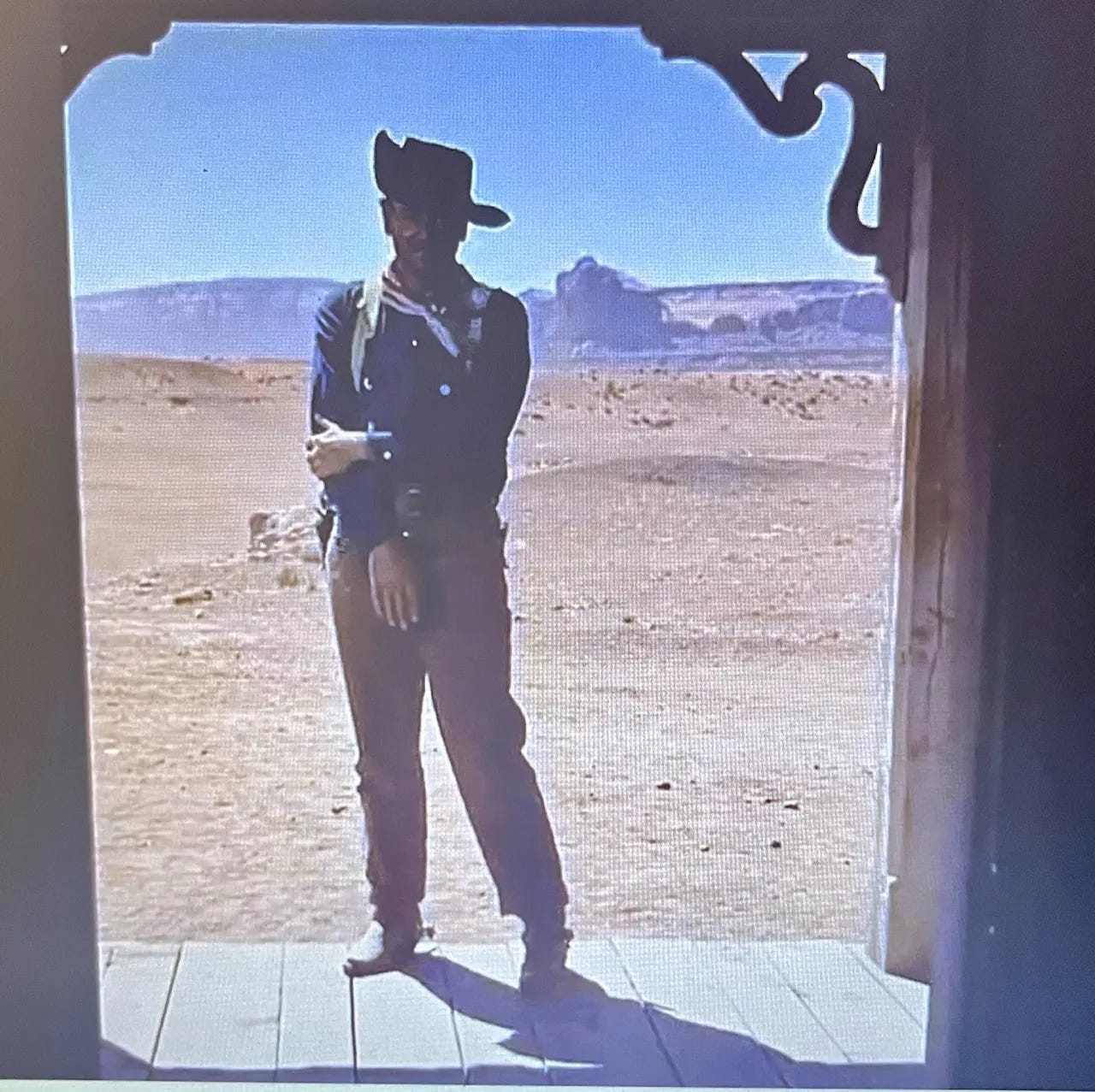

Without a doubt, the ending of John Ford’s epic 1956 film “The Searchers” is one of the most famous scenes in a Western, and cinema in general. In the film, John Wayne portrays Ethan Edwards, a Civil War veteran who spends years hunting his niece Debbie, who was abducted as a child by Comanche raiders. After a bloody battle, Ethan removes Debbie from the Comanches and he delivers Debbie to those she knew as a child.

(To many Texans, the story seems obviously based on the tale of Cynthia Parker. Cynthia was captured as a child by Comanche raiders and would become the wife of chief Peta Nocona and the mother of Quanah Parker, the last great Comanche chief. She was recaptured as an adult when Texas Rangers attacked a Comanche encampment along the Pease River near present-day Crowell. Remarkably, the band of Rangers would include both a future iconic rancher named Charles Goodnight and a future iconic Texas governor, university president, and university namesake in Lawrence Sullivan “Sul” Ross. It is an eternal debate as to whether the Rangers “saving” Cynthia Parker was the right thing to do. The remainder of her life was complicated, to say the least. For what it’s worth, the notes on “The Searchers” maintain that Parker’s story was only one of many child abductions studied by author Alan Le May in his work writing the novel from which the film was adapted.)

In the final moments of the film, everyone walks into the house. Everyone except for Ethan, that is. John Ford, ever the iconic filmmaker, cues up the harmony of the famed cowboy vocal group Sons of the Pioneers and they sing “ride away, ride away, ride away…” It is haunting. Ethan clearly feels set apart from all the others. He watches them for a moment and stares into the house. Then, he turns away. As he strides back towards his horse, the door swings shut. The screen goes black. “THE END” flashes.

It is incredible film-making. It is also terribly sad. Ethan Edwards turns his hunt for his niece (and his related hatred for the Comanche people) into an obsession. That obsession leads down a path of brutality in the film. He devotes his life to finding his niece and he finds her, but he loses more than a little of his humanity along the way. His choices leave him alone in the end. In the final scene, Ford depicts a man who is unwilling or unable to join his friends and loved ones. The spirit of family and community is either no longer within him or he feels unworthy of that spirit. Either way, the effect is the same. He strides away. His future is unknown to the viewer but the message is that it will be a solitary one.

The Western is sometimes criticized as shallow, two-dimensional storytelling in film and literature. I could debate that all day long with the most voracious critics of the Western. In part, that critique results from judging a genre by its lowest common denominator. There are plenty of other genres that are embarrassed by the worst stories among them and the Western is no different. Indeed, many Westerns contain unimaginative, formulaic, and fantastical plots. But those are not the ONLY stories told in the Western. Films like “The Searchers” tell complex narratives with more than a few shades of gray between black and white. On the surface, it is easy to look at Ethan Edwards and see a bold, daring, heroic figure. He was the archetype of the “rugged individualist” unafraid to face challenges and set out alone. A hero was needed, he rose to the challenge, he saved the day, and the movie ends. One need not be a trained film critic to see that there’s more to the story of Ethan Edwards than that. John Ford shows complicated, sad, and lonely elements to the character.

I have written in the past about the perils of “rugged individualism” and there are few better examples of the peril than that final scene of “The Searchers.” Ethan Edwards gave everything he had to search for his niece and avenge the bloody raid on his people. In the end, he was left with only that.

In my prior essay in the “American Idol” series, my friend Jerod McDaniel made a worthy observation in the comments to my essay on Facebook. He pointed out that there is an internal struggle that comes with the romantic isolation of the West. People (individually and collectively) need heroes. We long for heroes and thus we attempt to create heroism out of the romantic isolation of our own lives. If you need a hero for your story, who better than yourself? We are so tough and bold that we don’t NEED other people. We can go it alone. We can brave any challenge or danger that besets us. We are just like the brave heroes who settled the frontier before us! That can be a powerful feeling. When the spring winds howl, when the dust or hail storms rage, when a year’s worth of rain comes in a week, or when the native flora and fauna are predisposed to spines, stingers, and poison, it can be helpful to valiantly channel the spirit of your forefathers in the West as a motivational tactic.

But as Jerod and I discussed, these concepts can be both powerful and toxic, depending on how they are used. We can channel the heroism, romance, and idealism of the cowboy into a force for positivity in our lives and in our communities. That is something worthwile and admirable. But we must be careful not to channel those qualities the wrong way and end up a tragic, lonely figure like Ethan Edwards. Our communities are worse off when these qualities are emphasized in the wrong manner. It creates a false impression for others who are watching from us and hoping to be inspired by us, be it our peers or younger generations. We want them to see a worthwhile hero, not an ultimately tragic and lonely one. It also hurts our own mental health, leading us to believe that we are too tough, we don’t need anyone’s help, and we are the hero of our own story. That is all well and good until we crack under the strain and pressure or we realize too late that we’ve isolated ourselves from all the good things in life and become tragic and lonely, no better than Ethan Edwards walking away from his people.

James Decker is the Mayor of Stamford, Texas and the creator of the West of 98 website and the “Rural Church and State” and “West of 98” podcasts. Contact James and subscribe to these essays at westof98.substack.com and subscribe to him wherever podcasts are found. Check out the West of 98 Bookstore with book lists for essential reads here.

The hero who rides away into the sunset misses out on community and family, and at the same time shirks his responsibility to the same. Its not enough to bring the cows home when they get out. You have to put things in order, fix the fence and make sure they are cared for.

Louis L'Amour's best hero is, IMO, Bendigo Shafter. And I often quote what Louis has him say about community and responsibility.